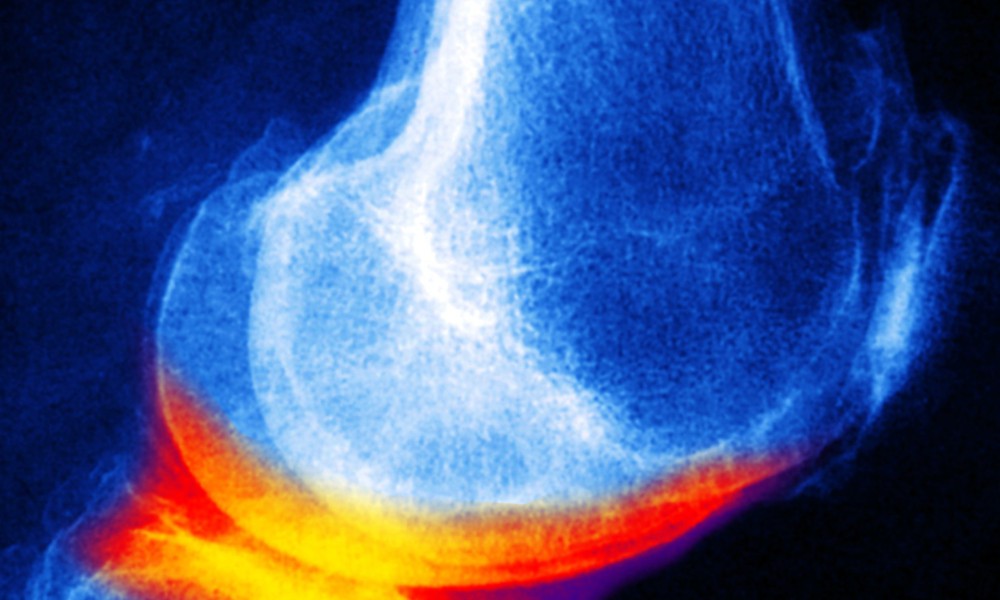

What happens in joints when osteoarthritis sets in?

Things would be easier if we were mice. Then there would be a treatment for osteoarthritis that would allow many of us to avoid pain in our knees, hips and other joints.

“In mice, we know how to slow down cartilage degradation. But unfortunately, in humans, everything is a lot more complicated.”

So says André Struglics, osteoarthritis researcher at BMC in Lund. The fact is that although there are so many osteoarthritis sufferers, and in spite of the disease’s considerable impact on the economy, we still have little detailed knowledge of what happens in the joints when osteoarthritis sets in.

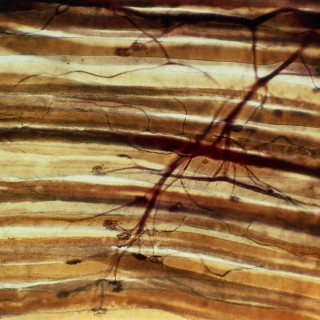

Osteoarthritis was previously known as degenerative joint disease. This is a misleading term which is no longer used, as the cartilage – the shock-absorbing cushioning in the joints – is not worn down through use but on the contrary benefits from exercise. However, a direct injury to the knee, for example, often leads to osteoarthritis, which means that the disease also affects younger people.

“A young athlete can recover well after a knee injury, but ten years later he or she may develop pain in the knee. X-rays then reveal ongoing osteoarthritis.”

He and his colleagues are now trying to look into the ‘black hole’, the period between the knee injury and the osteoarthritis diagnosis in which the disease has started but is not yet noticed by the patient. A group of patients with knee injuries have been summoned regularly since their injury to provide samples, answer interview questions and have X-ray and MRI scans taken of their knee joints.

Now these patients are approaching the end of the period in which the disease remains hidden and does not cause any symptoms. Some of the former knee patients may soon be affected by the first osteoarthritic pains.

“We can expect half the group to get osteoarthritis that will worsen over time, whereas the others will either get a mild form of osteoarthritis or will remain free of problems. We hope that all the samples we have taken will teach us more about the early stages of the disease, and will also provide us with markers showing when it sets in”, says André Struglics.

To see this at an early stage would be good, he thinks – because even though we do not yet have any drugs against osteoarthritis, we do have good guidelines for patients. By losing weight, doing appropriate physiotherapy and exercise, and changing work duties if one’s job is wearing on the knees, the disease can be prevented from becoming too debilitating.

A protein called aggrecan may be a possible marker for the disease. Aggrecan helps cartilage to absorb water and become suitably elastic. The aggrecan is one of the first proteins to be broken down in osteoarthritis. We know today which enzyme is responsible for destroying the aggrecan, and we have been able to slow down its effect in mice with osteoarthritis. In humans, however, the relevant enzyme fulfils many functions and can therefore not be blocked without side-effects.

Skeletal remains from the Stone Age show changes indicative of osteoarthritis, so the disease seems to have been around for a long time. But today we reach a more advanced age than before and would prefer to maintain an active lifestyle including mountain hikes, rounds of golf and walks in the woods. This is why approximately 15 000 hip replacement operations are carried out every year in Sweden, and about as many patients get new knee joints.

André Struglics is hopeful that a remedy for osteoarthritis will be found in the future. Perhaps a researcher will stumble upon the solution more or less by chance, or perhaps the disease can be divided into various subgroups that can be treated in different ways. But he thinks that research into osteoarthritis gets too little support in comparison to other common diseases.

“Osteoarthritis isn’t a direct cause of death, it’s true, but the disease does cause both great suffering and major costs to healthcare and through sick leave”, he points out.

Text: Ingela Björck

Published: 2013